Tribal History

In the history of the tribe, the majority of families have lived in both worlds since colonial times, and many of the clans have been able to hold citizenship rights in the states in which they resided. This was not always the case with all of the tribal descendants, nor with our tribal kin and treaty nations that had formal relations with the United States government. To answer questions that have arisen regarding the heritage, culture, and history of the Whitetop Nation, we have provided an abbreviated history. When researching the Indigenous History of the Sizemores, it is essential to conduct thorough research, explore your genealogical heritage, and remember that the Bureau of Indian Affairs (BIA) does not recognize splinter groups. We have provided an abbreviated history of the Whitetop Nation (www.whitetopnation.org) below to help you on your research.

The most essential supporting document is the Guion Miller Commission applications [1],[2],[3],[4] also known as the Eastern Cherokee Applications (ECAs), Case #417 of George Washington Plummer, which states that the Sizemores have native blood and tradition but no known connection to the Cherokee at the time of the ruling. Special Agent Miller further states that he believes they are either Virginia Native or Catawba. However, according to the Catawba official rolls and unofficial rolls, there are no known Sizemore connections from the time of Old Ned, father of George All, brother to Susannah Caroline Brock nee Sizemore, Uncle to Dr. Johnny Gourd Sizemore, and numerous others. This means that the listed families are an American Indian tribe from the state of Virginia.

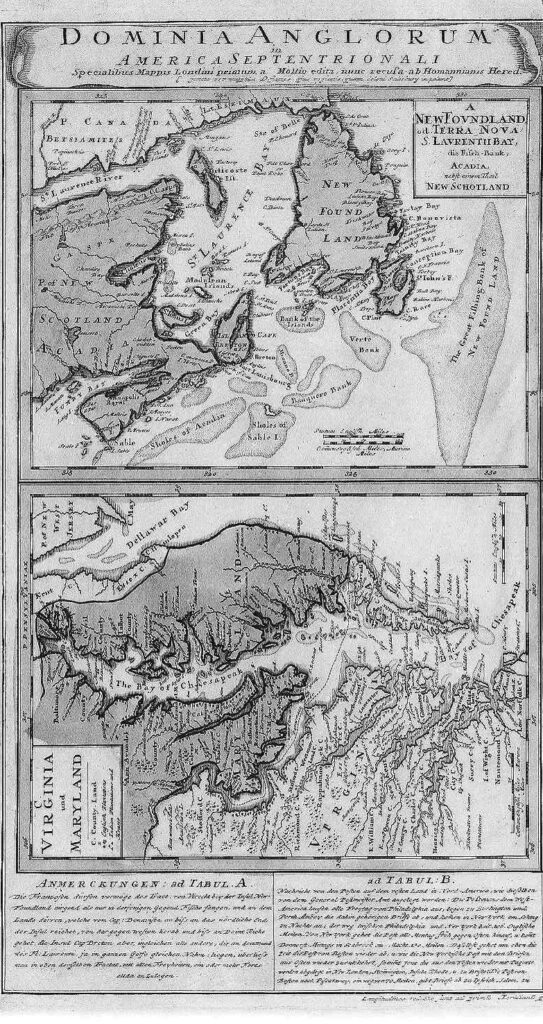

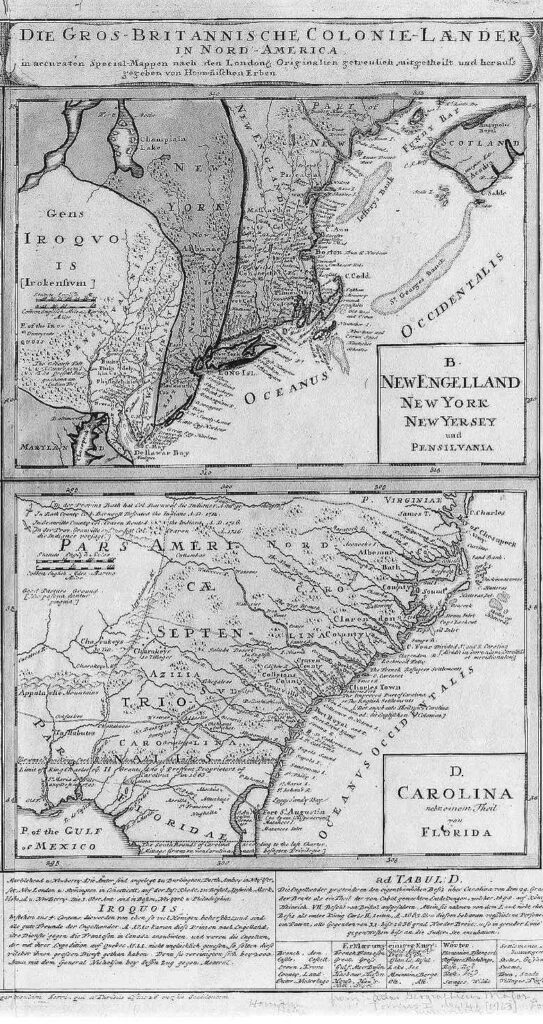

According to research done by the Whitetop Nation, the tribe is that of the Moheton/Moneton, as determined by explorers including John Smith[5],[6], Harris[7], Lederer[8], Col. Woods[9], Batts and Fallow[10],[11], Fallum’s Journal, Federer[12], Alvord and Bidgood[13], and Walker[14]. Anthropologists such as Gist and his Journals[15], McGee[16], Mooney[17],[18], Meeker[19], Tooker[20], Hana[21], Summers[22], Griffin[23],[24], Beckner[25], Brown[26], Bushnell[27],[28], Dorsey[29],[30], Sturtevant[31], Swanton[32],[33],[34], Lesser[35], Balderson[36], Hale[37], Briceland[38],[39], Maslowski[40], Heribeto[41], Taylor[42], Eastman[43], Davis and Ward[44], Demallie[45], Goggard,[46] Eubanks and Dumas[47], Rankin[48], and Voegelin[49] also confirm the tribe being of the Moheton/Moneton descent. These explorers and anthropologists have shown that the Moheton/Moneton lived in the area extending from the headwaters of the New/Wood River in the vicinity of Whitetop Mountain and near Saltsville, Virginia[50] to the falls located where the New River merges with the Gauley River. This is vital, as the Sizemore line continues to revere the homeland of the Sizemores as the Whitetop Mountain region, the home of the tribal Nation. Whitetop Mountain holds special significance as Chief Blevins named the confederacy of clans after this mountain, where Edward ‘Old Ned’ Sizemore was raised and lived. Anthropologists have also noted the presence of salt and other indigenous minerals found within the region, which have been passed down through the Sizemore lineage and migration paths. The anthropologists point to the surrounding tribes as relations, such as Mooney and McGee, stating that the Moheton belonged to the Monacan Confederation and was one of the numerous tribes over the Allegheny Ridge that John Smith mentions in his journals, which he used to draw his map of Virginia dated 1624.

The Whitetop Band of Indians, also known as the Whitetop Band of Laurel Creek Indians and the Whitetop Band of Cherokee Indians, was established in 1896 when Chief William Harrison Blevins was elected the Principal Chief by the other clan chiefs[51],[52] . After Chief Blevins died in 1924, the tribe reverted to the clan rule that had dominated its family history. Over the next 80 years, clan rule was maintained, with several attempts by various clan heads to unite that ultimately failed. Several clan heads continued to petition the Cherokee and neighboring tribes for admission to their rolls, as they remained convinced by the Special Agents’ claims that the families were on Cherokee land and that they were their lineage. Numerous clan heads attempted to come together for recognition. However, they continued to engage in infighting rather than working together to achieve full recognition.

It is essential to reiterate that the BIA does not recognize splinter groups.[53] In the 1980s and early 1990s, there was a resurgence in the clan heads seeking their tribal recognition. The reformation of the Whitetop Band of Native Indians is the largest clanship merger of the tribe since 1924, maintaining the direct link to Chief Blevins and the other Clan Chiefs. In the early 2000s, several clan heads entered into discussion to band together for the recognition that was originally sought in 1896. While the clan heads discussed merging in the early 2000s, it was not officially documented as The Tribe of the Whitetop Band of Native Indians (WBNI) being re-formed until 2010-2012. It was registered in Kentucky in 2013 after the adoption of its first bylaws. This is important as, on December 6, 2014, several Elders, in keeping with the clanship rule and mentality, had issues with the by-laws at the time that required specific prayer, and decided to break away, forming what is known today as the New River Catawba in North Carolina[54], a name they adopted in 2020. The New River Catawba originally registered with the Secretary of State of North Carolina as the Appomattoc Tribe of the Canawhay River on April 8th, 2015, and maintains the closed Facebook group entitled the New River Indians Information Center. Nevertheless, the WBNI continued in Manchester, Kentucky. Then, May 1, 2020 the then Chief announces they are leaving yet maintains power until July 28, 2020, this is the second splinter group from the WBNI, and a new group formed, which is now known as the Southeastern Kentucky Saponi Nation[55]. This group was registered with the state of Kentucky on December 21, 2020. The group maintains a closed Facebook page in addition to their website.

WBNI continued its existence. In 2023, WBNI decided to leave clanship rule behind them by forming a Constitutional convention and followed the regulations outlined in the Indian Reorganization Act of 1934 by adopting its official constitution in May of 2023[56]. At this time, WBNI voted to change the tribe’s name to Whitetop Nation to reflect the tribe’s history. In so doing, Whitetop Nation acknowledged the anthropologists’ and explorers’ documentation of the tribal heritage, being that of the Moheton/Moneton tribe on the New/Woods River[57]. Whitetop Nation maintained and retained and still maintains and retains the name that Chief William Harrison Blevins gave to confederated clans, that of the Whitetop Nation[58]. Whitetop Nation also continues to recognize the federal government’s recognition of Whitetop Nation’s indigenous heritage and culture as the direct descendants of the WBNI established in 1896 and recognized by Special Agent Miller and the Eastern Cherokee Nation[59].

The Whitetop Nation retains its corporate headquarters in Georgetown, Kentucky until its council votes on a place to relocate the nation’s capital. Whitetop Nation is following the BIA requirements for recognition[60]. Whitetop Nation has also established communication with other federally recognized tribes regarding recognition efforts and restructured the tribe’s Office of Genealogy, which is working diligently and with great detail to finalize Whitetop Nation’s founding rolls.

If you have any questions about how to apply as a citizen of the Whitetop Nation, and if you are of lineage descent, please get in touch with applications@whitetopnation.org

Footnotes

[1] Fold3, US, Eastern Cherokee Applications of the U.S. Court of Claims, 1906-1910 (https:///www.fold3.com/publications/73/us-eastern-cherokee-application-1906-1909 : accessed Jun 9, 2025), database and images, https://www.fold3.com/publication/73/us-eastern-cherokee-applications-1906-1909

[2] National Archives, M1104, Eastern Cherokee Applications of the U.S. Court of Claims, 1906-1909 (National Archives Identifier 301643) : accessed Jun 9, 2025, database and images, https://www.archives.gov/files/research/microfilm/m1104.pdf George Washington Plummer case #417 is found as job number 09-013 under the NARA catalog id of 2110769.

[3] National Archives, M685, Records Relating to Enrollment of Eastern Cherokee by Guion Miller, 1908-1910 (National Archives Identifier 300329): accessed Jun 9, 2025, database and images, https://www.archives.gov/files/research/microfilm/m685.pdf

[4] Jordan, J. W. (2008). Cherokee By Blood: Records of Eastern Cherokee Ancestry in the U.S. Court of Claims 1906-1910. Vol. I of 9, Heritage Books:Westminster ISBN: 978-1-55613-048-9 The George Washington Plummer filing numbered 417 lists the reasoning of the Sizemores. In this case Guion miller states: “While it seems certain that there has been a tradition of Indian blood, the testimony is entirely too indefinite to establish a connection with the Eastern Cherokee Indians at the time of the Treaty of 1835. The locality where these claimants and their ancestors are show to have been living from a period considerably prior to 1800 up to the present time, is a territory that, during this time, has not been frequented by Cherokee Indians. It is a region much more likely to have been occupied by Indians from Va. Or the Catawba Indians who ranged from South Carolina up through North Carolina into Va. It is also significant that the name Sizemore does not appear upon any of the Cherokee rolls. For the foregoing reasons, all of these Sizemore claims have been rejected.” pp126-132.

[5] Smith, John (1624). The Generall Historie of Virginia, New-England, and the Summer Isles: With the Names of the Adventurers, Planters, and Governours from Their First Beginning, Ano: 1584. To This Present 1624. With the Procedings of Those Severall Colonies and the Accidents That Befell Them in All Their Journyes and Discoveries. Also the Maps and Descriptions of All Those Countryes, Their Commodities, People, Government, Customes, and Religion Yet Knowne. Divided into Sixe Bookes. By Captaine Iohn Smith, Sometymes Governour in Those Countryes & Admirall of New England. London: I.D. and I.H.

[6] Smith, John (1606). Map of Virginia. Retrieved from National Park Service on Jun 9, 2025 from: https://www.nps.gov/articles/000/smith-map-of-virginia.htm

[7] Mentioned in the House of Burgess to form an expedition over the falls.

[8] Baronet, William T. (1672). The Discoveries of John Lederer, In three several Marches from Virginia, to the West of Carolina, And other parts of the Continent: Begun in March 1669, and ended in September 1670. Together with a General Map of the whole Territory which he traversed. London: J.C. for Samuel Heyrick

[9] Col. Abraham Woods conducted numerous expeditions into what has become known as the New River Valley. His first expedition was in 1650 in which he was joined by fur trader and merchant Edward Bland.

Bland, E. & Woods, A. (1650). Transcription Source: Bland, Edward, Sackford Brewster, and Elias Pennant. The discovery of New Brittaine. Began August 27. anno Dom. London, Printed by T. Harper for J. Stephenson, 1651. https://www.loc.gov/item/04029775/

[10] Fallows, Arthur. (1853). The Journal & Relation of a New Disccovery made behind the Apuleian Mountains to the West of Virginia. Documents Relative to the Colonial History of the State of New York, vol. III, pp. 193-197 New York

[11] Bushnell, D. I. (1907). A Journal from Virginia Beyond the Appalachian Mountains in Septr., 1671, Sent to the Royal Society by Mr. Clayton, and Read Aug. 1 1688 before the Said Society. The William and Mary College Quarterly Historical Magazine. Vol. 15, No. 4 (Apr. 1907), pp. 235-241

[12] Lederer, J. (1672). The Discoveries of John Lederer, in Three Several Marches from Virginia to the West of Carolina, and other parts of the Continent, Begun in March 1669, and ended in September 1670. London 1672; reprinted, Rochester, N.Y. 1902

[13] Alvord, C. W. & Bidgood, L. (1912). The First Explorations of the Trans-Alleghany Region by the Virginians 1650-1674. Cleveland, OH: Arthur H. Clark Company

[14] Henderson, Archibald. (1931). Dr. Thomas Walker and the Loyal Company of Virginia. American Antiquarian Society. April. 1931

[15] Darlington, W. M. (1882-1893). Christopher Gist’s Journals. Compiled by William M. Darlington. Retrieved from the Darlington Digital Library at the University of Pittsburgh https://digital.library.pitt.edu/collection/christopher-gists-journals-william-m-darlington

[16] McGee, W. J. (1897). The Siouan Indians

[17] Mooney, J. (1895). The Siouan tribes of the East. Bureau of American Ethnology Bulletin

[18] Mooney, J. (1894). The Siouan tribes of the East (No. 22). US Government Printing Office

[19] Meeker, L. L. (1901). Siouan Mythological Tales. The Journal of American Folklore, 14(54), 161–164 https://doi.org/10.2307/533626

[20] Tooker, W. W. (1895). The Algonquian Appellatives of the Siouan tribes of virginia. American Anthropologist, 8(4), 376-392

[21] Hanna (1911)

[22] Summers, Lewis P. (1929). The Expedition of Batts and Fallam: A Journey from Virginia to beyond the Appalachin Mountains, September, 1671. From Annals of Southwest Virginia, 1769-1800.

[23] Griffin, J. B. (1942). On the Historic Location of the Tutelo and the Mohetan in the Ohio Valley. American Anthropologist, 44(2), 275–280. http://www.jstor.org/stable/663025

[24] Griffin, J. B. (1945). An interpretation of Siouan archaeology in the piedmont of North Carolina and Virginia. American Antiquity, 10(4), 321-330

[25] Beckner, L. (1948). KENTUCKY BEFORE BOONE: The Siouan People. The Register of the Kentucky Historical Society, 46(154), 384–396. http://www.jstor.org/stable/23372671

[26] Brown, R. M. (1937). A Sketch of the Early History of South-Western Virginia. The William and Mary College Quarterly Historical Magazine, 17(4), 501–513. https://doi.org/10.2307/1923744

[27] Bushnell, David I. (1921). Native Cemeteries and Forms of Burial East of the Mississippi. American Anthropologist, Jul-Sep 1921, New Series, Vol. 23, No. 3 (Jul-Sep 1921), pp. 366-370. https://www.jstor.org/stable/660550

[28] Bushnell, Daivd I. (1940). Virginia before Jamestown. Essays in Historical Anthropology of North America. May 25, 1940. Smithsonian Institute: City of Washington

[29] Dorsey, J. O. (1897). Siouan sociology: a posthumous paper (No. 3). US Government Printing Office

[30] Dorsey, J. O. (1886). Migrations of Siouan tribes. The American Naturalist, 20(3), 211-222

[31] Sturtevant, W. C. (1959). The Discoveries of John Lederer, with Unpublished Letters by and about Lederer to Governor John Winthrop, Jr., and an Essay on the Indians of Lederer’s Discoveries by Douglas L. Rights and William P. Cumming

[32] Swanton, J. R. (1936). Early history of the eastern Siouan tribes. In Essays in anthropology presented to AL Kroeber (pp. 371-81)

[33] Swanton, J. R. (1923). New light on the early history of the Siouan peoples. Journal of the Washington Academy of Sciences, 13(3), 33-43

[34] Swanton, J. R. (1916). Some information from Spanish sources regarding the Siouan tribes of the East. Journal of the Washington Academy of Sciences, 6(17), 609–612. http://www.jstor.org/stable/24521245

[35] Lesser, A. (1958). Siouan Kinshop. Columbia University ProQuest Dissertations & Theses

[36] Balderson, Walter. (1973). Wonderful West Virginia articles “Allegeny” and “Wonderfull West Virginia” September 1973, pp 30, “Walley Falls of Old”

[37] Hale, Horatio. (1868). Development of Language

[38] Briceland, Alan. (1987). Westward from Virginia: The Exploration of the Virginia-Carolina Frontier, 1650-1710. Charlottesville: University Press of Virginia. https://archive.org/details/westwardfromvirg0000bric

[39] Briceland, A. V. (1979). The Search for Edward Bland’s New Britain. The Virginia Magazine of History and Biography, 87(2), 131–157. http://www.jstor.org/stable/4248294

[40] Maslowski, Robert. (ukn). Fort Ancient, The Moneton, and Virginia Siouan. Retrieved June 9, 2025 from https://www.academia.edu/124426347/Fort_Ancient_the_Moneton_and_Virginia_Siouan

[41] Heriberto, D. (2002). A Saponi by any other Name is Still a Siouan. https://doi.org/10.17953

[42] Taylor, C. A. (1906). The Social and Religious Status of Siouan Women Studied in the Light of the History and Environment of the Siouan Indians (Doctoral dissertation, University of Kansas)

[43] Eastman, J. M. (1999). The Sara and Dan River Peoples: Siouan Communities in North Carolina Interior Piedmont from A.D. 1000 to A.D. 1700. University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill ProQuest Dissertations & Theses

[44] Davis, R. P. S., & Ward, H. T. (1991). THE EVOLUTION OF SIOUAN COMMUNITIES IN PIEDMONT NORTH CAROLINA. Southeastern Archaeology, 10(1), 40–53. http://www.jstor.org/stable/40712940

[45] DeMallie, Raymon. (2004). “Tutelo and Neighboring Groups”, in Fogelson, Raymond D. Handbook of North American Indians, Vol. 14: Southeast, Washington, DC: Smithsonian Institution, pp. 286–300

[46] Goddard, I. (2005). The Indigenous Languages of the Southeast. Anthropological Linguistics, 47(1), 1–60 http://www.jstor.org/stable/25132315

[47] Dumas, A. & Eubanks P. (2021). Salt in Eastern North America and the Caribbean: History and Archaeology

[48] Rankin, R. L. (2006). Siouan Languages. DOI: 10.1016/B0-08-044854-2/02277-X

[49] Voegelin, C. F. (1941). Internal relationships of Siouan languages. American Anthropologist, 43(2), 246-249

[50] Dumas, A & Eubanks P. (2021). Salt in Eastern North America and the Caribbean: History and Archaeology

[51] Fold3, US, Eastern Cherokee Applications of the U.S. Court of Claims, 1906-1910 (https:///www.fold3.com/publications/73/us-eastern-cherokee-application-1906-1909 : accessed Jun 9, 2025), database and images, https://www.fold3.com/publication/73/us-eastern-cherokee-applications-1906-1909. Case 8584.

[52] Jordan, J. W. (2008). Cherokee By Blood: Records of Eastern Cherokee Ancestry in the U.S. Court of Claims 1906-1910. Vol. I of 9, Heritage Books: Westminster ISBN: 978-1-55613-048-9 Case 8584 pp.169-172

[53] Title 25 Ch. I Subchapter F Part 83.4b “A splinter group, political faction, community, or entity of any character that separates from the main body of a currently federally recognized Indian tribe, petitioner, or previous petitioner unless the entity can clearly demonstrate it has functioned from 1900 until the present as a politically autonomous community and meets § 83.11(f), even though some have regarded them as part of or associated in some manner with a federally recognized Indian tribe…”

[54] New River Catawba, www.newrivercatawba.org

[55] Southeastern Kentucky Saponi Nation, www.sekysaponi.org

[56] Whitetop Nation Constitution of 2023

[57] Mooney, J. (1895). The Siouan tribes of the East. Bureau of American Ethnology Bulletin; McGee, W. J. (1897). The Siouan Indians; Swanton, J. R. (1916). Some information from Spanish sources regarding the Siouan tribes of the East. Journal of the Washington Academy of Sciences, 6(17), 609–612 http://www.jstor.org/stable/24521245; Swanton, J. R. (1923). New light on the early history of the Siouan peoples. Journal of the Washington Academy of Sciences, 13(3), 33-43; Swanton, J. R. (1936). Early history of the eastern Siouan tribes. In Essays in anthropology presented to AL Kroeber (pp. 371-81); Heriberto, D. (2002). A Saponi by any other Name is Still a Siouan. https://doi.org/10.17953;

[58] Fold3, US, Eastern Cherokee Applications of the U.S. Court of Claims, 1906-1910 (https:///www.fold3.com/publications/73/us-eastern-cherokee-application-1906-1909 : accessed Jun 9, 2025), database and images, https://www.fold3.com/publication/73/us-eastern-cherokee-applications-1906-1909

[59] Jordan, J. W. (2008). Cherokee By Blood: Records of Eastern Cherokee Ancestry in the U.S. Court of Claims 1906-1910. Vol. I of 9, Heritage Books: Westminster ISBN: 978-1-55613-048-9 The George Washington Plummer filing numbered 417 lists the reasoning of the Sizemores. In this case Guion miller states: “While it seems certain that there has been a tradition of Indian blood, the testimony is entirely too indefinite to establish a connection with the Eastern Cherokee Indians at the time of the Treaty of 1835. The locality where these claimants and their ancestors are show to have been living from a period considerably prior to 1800 up to the present time, is a territory that, during this time, has not been frequented by Cherokee Indians. It is a region much more likely to have been occupied by Indians from Va. Or the Catawba Indians who ranged from South Carolina up through North Carolina into Va. It is also significant that the name Sizemore does not appear upon any of the Cherokee rolls. For the foregoing reasons, all of these Sizemore claims have been rejected.” pg 126-132